Hope responded, "I don't have to tell you that this is rather a surprise to me. I didn't read it in the paper until three weeks ago, you know, but it is really wonderful, and I know that (Bing) Crosby will never believe it." Never without a joke, he added, "Of course, he hasn't received anything like this since Gen. Lee gave him his (medal) for leading the retreat from Bull Run." Hope responded, "I don't have to tell you that this is rather a surprise to me. I didn't read it in the paper until three weeks ago, you know, but it is really wonderful, and I know that (Bing) Crosby will never believe it." Never without a joke, he added, "Of course, he hasn't received anything like this since Gen. Lee gave him his (medal) for leading the retreat from Bull Run."

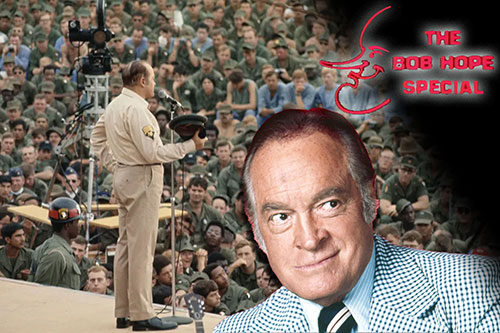

Hope's beloved Christmas show started in 1948, with his "last one" scheduled in 1972 in Vietnam. But every Christmas after that, he continued to entertain U.S. troops. He spent so much time in the field that Congress made him the nation's first honorary veteran in 1997, at 94.

Called "America's No. 1 Soldier in Greasepaint" and "GI Bob," Hope made a few more public appearances, celebrating his 100th birthday in May 2003. He died two months later.

Hope was the fifth of seven sons of a stonemason and a former Welsh concert singer; his family immigrated to the United States when he was four years old. He grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, manifesting the first signs of his vocation at age 10 when he won a Charlie Chaplin imitation contest. After a series of odd jobs, including amateur boxer, Hope during his late teens embarked on an entertainment career and later performed with a succession of partners in vaudeville. He first appeared on Broadway in Sidewalks of New York (1927), and after additional work in vaudeville and a failed Hollywood screen test, he landed his first substantial stage role in the Jerome Kern musical Roberta (1933). During the mid-1930s he starred in a series of comedy shorts and found increasing success in radio, a medium well-suited to his loquacious style. Hope made his feature-film debut in The Big Broadcast of 1938 (1938), in which he first sang his signature tune “Thanks for the Memory,” and he launched the long-running The Bob Hope Show on radio in that same year. By the end of the decade, Hope was one of America’s most popular comics.

Just as silent films had popularized physical and slapstick comedy, the encroachment of sound motion pictures and radio during the 1930s paved the way for Hope’s style of brash verbal comedy. Although a bug-eyed double take is a familiar Hope trademark, most of his comedy relied on quips and wisecracks delivered at a breakneck pace. His persona was that of transparent bravado, glib repartee, and ingratiating mediocrity—a smart aleck who cowers at the slightest threat. He did not elicit audience sympathy and was less likely to win the girl at the end of a film than he was to wind up the buffoonish victim of some quagmire of his own making. By allowing the audience to feel superior to him, Hope was one of the few comic performers to sustain a successful career built upon a largely unsympathetic character.

Bob Hope with men of X Corps, Wonsan, Korea, 1950.

During World War II Hope traveled extensively to entertain troops overseas and at home; most of his war-era radio shows were broadcast from military bases throughout the world. Because of his similar tours during American military involvement in Korea, Vietnam, and the Persian Gulf over subsequent decades, Hope became as renowned for his armed forces shows as for his accomplishments as an entertainer. In 1997 the U.S. Congress recognized his efforts by naming him the first “Honorary Veteran” in U.S. history. Hope called it “the greatest honor I have ever received.” His other honours and awards included an honorary Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE), an honorary British knighthood, the Congressional Gold Medal, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and five special Academy Awards for humanitarian services and contributions to the film industry.

Awards notwithstanding, Hope endured harsh criticism throughout his career both for his politics and for his reluctance to challenge himself as a performer. As his films became increasingly tired and formulaic in the 1960s, so too did his hawkish politics become out of sync with the American mood during the Vietnam War era. Young Americans, unfamiliar with the glib wisecracking Hope of the 1940s films, now derided him as the embodiment of the “Establishment.” He was probably seen at his best during these years in live performance, where, free from the need to be topical, he could deliver a largely spontaneous show built around the vast mental warehouse of jokes that he had compiled over the decades.

By the late 1970s Hope’s status as a major comic had been restored somewhat by prominent critics and directors (such as Woody Allen) who lavished praise upon his films of the 1940s and early ’50s. To his harshest critics, Hope will probably remain little more than a capable mouthpiece for his staff of comedy writers. To admirers, he represents a vital component in American comedy history and personifies the comic tastes of the World War II generation, by whom wit and wordplay were highly valued.

|

Hope responded, "I don't have to tell you that this is rather a surprise to me. I didn't read it in the paper until three weeks ago, you know, but it is really wonderful, and I know that (Bing) Crosby will never believe it." Never without a joke, he added, "Of course, he hasn't received anything like this since Gen. Lee gave him his (medal) for leading the retreat from Bull Run."

Hope responded, "I don't have to tell you that this is rather a surprise to me. I didn't read it in the paper until three weeks ago, you know, but it is really wonderful, and I know that (Bing) Crosby will never believe it." Never without a joke, he added, "Of course, he hasn't received anything like this since Gen. Lee gave him his (medal) for leading the retreat from Bull Run."