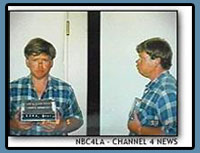

A mug shot of Russell Eugene Weston, who opened fire inside the U.S. Capitol building Friday. SuspectRussell Weston remains in guarded condition with gunshot wounds from Capitol Police officers. Russell is known for prior threats against the President of the United States. A mug shot of Russell Eugene Weston, who opened fire inside the U.S. Capitol building Friday. SuspectRussell Weston remains in guarded condition with gunshot wounds from Capitol Police officers. Russell is known for prior threats against the President of the United States.

The condition of the suspect, Russell E. Weston Jr., 41, from Rimini, Mont., was upgraded from critical to serious during the day. “His cardiac status has improved,” said D.C. General Hospital spokeswoman Donna Lewis Johnson.Weston was shot in the chest, arms, thigh and buttocks and brought down in a furious exchange of gunfire with Gibson.

Authorities arranged a hearing in absentia for Weston on Monday in federal court, a few blocks from the Capitol. Papers filed in court in the District of Columbia on Saturday charged him with killing the two officers; the purpose of Monday’s hearing is to bring the case into federal court. Authorities arranged a hearing in absentia for Weston on Monday in federal court, a few blocks from the Capitol. Papers filed in court in the District of Columbia on Saturday charged him with killing the two officers; the purpose of Monday’s hearing is to bring the case into federal court.

SUSPECT CONFUSED

The shooting suspect, Russell E. Weston Jr., remained in stable condition Tuesday but faced further surgery. On Monday, U.S. Magistrate Judge Deborah Robinson said she would evaluate Weston’s case “day by day,” with arraignment and additional charges possibly delayed until he is healthy enough to appear in court. Weston already is charged with murder in the Friday gunfight that killed the two officers and wounded a tourist. The shooting suspect, Russell E. Weston Jr., remained in stable condition Tuesday but faced further surgery. On Monday, U.S. Magistrate Judge Deborah Robinson said she would evaluate Weston’s case “day by day,” with arraignment and additional charges possibly delayed until he is healthy enough to appear in court. Weston already is charged with murder in the Friday gunfight that killed the two officers and wounded a tourist.

Amid speculation that Weston — once diagnosed as suffering from paranoid schizophrenia — could plead insanity in his defense, prosecutors said it was much too early to make any definitive decisions about their case or whether they would seek the death penalty.

“We’re preparing for all possibilities,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Channing Phillips said.

Weston, 41, was being kept under sedation and heavily guarded in his hospital bed at D.C. General Hospital. Dr. Norma Smalls said wounds caused by bullets that tore through bones and blood vessels in an arm and leg required more surgery and risked causing a blood clot that could threaten his life.

Weston “is aware that he is a prisoner,” Smalls said. “We are able to speak to him, but there is some confusion on his part.”

Weston’s court-appointed lawyer, A.J. Kramer, said he had been able to speak with his new client for 45 minutes Monday morning but declined to discuss Weston’s condition or legal situation, other than to say, “He’s not in good shape” physically.

MOTIVE KEY TO INSANITY DEFENSE

Weston was diagnosed years ago as a paranoid schizophrenic who suffers from delusions. At times Weston believed the federal government was watching him through a neighbor’s satellite dish or had spiked his land with mines. He once pestered a guard at the CIA’s headquarters with claims that he and the president were clones.

Should Weston’s attorneys eventually decide to enter an insanity plea, such delusions may not be enough to make that case. Insanity is a legal classification that goes beyond a diagnosis of mental illness. Under federal law, to plead insanity it must be proven that a defendant suffers from severe mental illness and, at the time of the crime, was incapable of understanding the moral or criminal wrongfulness of what he or she did.

Russell Eugene Weston Jr. in a 1991 Montana sheriff's booking photo. He was charged at the time for drug possession. “We can have two paranoid schizophrenics committing the same act... and one could be found sane and one could be found criminally insane,” according to forensic psychiatrist Phillip Resnick, a consultant to prosecutors in the Unabomber and Oklahoma City bombing cases.

“Until you can find out his motive, and why he did what he did, you can’t know” whether a defendant qualifies as insane, Resnick said. If Weston’s lawyers decide to pursue an insanity claim, they first would ask a judge to order a 30-day psychiatric review, which probably would take place at the nearest federal prison, Phillips said.

Such defenses are difficult to prove, relying not just on psychiatric evaluation but on witnesses’ testimony and other evidence as well. Insanity defenses are rare, arising in about 1 percent of all criminal prosecutions, according to Dr. Paul Appelbaum, secretary of the American Psychiatric Association. When raised, the defense is only about 25 percent successful, he said.

For Russell Weston’s parents, the ordeal of being questioned by the federal officials is over, and now they are left alone with their grief and sorrow. NBC’s Ed Rabel reports.

Anyone found not guilty by reason of insanity would most likely be sent to a mental hospital instead of a prison.

WESTON’S PARENTS APOLOGIZE

Weston’s parents, Russell Sr. and Arbah Jo, said Monday they hadn't spoken to their son since the shooting. “I feel so bad about it,” Weston Sr. said on NBC, speaking from his home in Valmeyer, Ill. “I feel so bad for the people that he killed. I apologize to the nation.”

Weston’s father said his son had a long history of mental illness, starting after he graduated from high school.

To federal officials, Weston was a Secret Service nightmare. He visited CIA headquarters on July 29, 1996, sat with a CIA security officer and began to ramble, getting into “some pretty bizarre stuff,” according to a government official who spoke on condition of anonymity. Weston claimed to have been cloned at birth, said that Clinton had been cloned at birth and claimed Clinton may have played a role in the Kennedy assassination out of anger at Kennedy “for stealing his (Clinton’s) girlfriend, Marilyn Monroe.”

While Weston’s motive for shooting the police officers is unclear, agents recovered some evidence from Weston’s home: A logbook or diary and a voluminous amount of papers were recovered by FBI agents from his truck and home, according to law enforcement sources. They declined to describe the writings in detail, but there was an indication they revealed some instability. One law enforcement official said prosecutors did not want the writings discussed because they went to Weston’s state of mind and might aid defense attorneys.

Weston wrote several letters to Sen. Conrad Burns, R-Mont., MSNBC affiliate KERI in Helena, Mont., reported. Capitol police were reportedly investigating the contents of the undisclosed letters.

Murder Charges Filed in Capitol Rampage Murder Charges Filed in Capitol Rampage

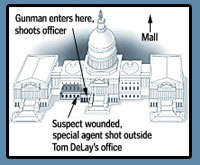

See Detailed Map

By Michael Grunwald and Cheryl W. Thompson

Washington Post Staff Writers

Russell Eugene Weston Jr., a former mental patient from Montana, was charged yesterday with murdering two U.S. Capitol Police officers during a rampage in the Capitol building that allegedly began when Weston walked up behind an officer and shot him point-blank in the back of the head.

Law enforcement sources and court documents added chilling new details yesterday about the Friday afternoon killings of Jacob J. Chestnut, 58, and John M. Gibson, 42, both 18-year veterans of the force. They said that after bursting through a Capitol security checkpoint and shooting Chestnut, Weston chased a screaming woman down a hallway until he was confronted by Gibson, who pushed the woman out of harm's way and exchanged deadly gunfire with the intruder.

Weston, 41, slipped into unconsciousness and was downgraded early yesterday from stable to critical condition after surgery Friday at D.C. General Hospital. Doctors said he had a "50-50" chance of survival. He was ordered held without bond yesterday during a brief hearing in D.C. Superior Court.

An FBI agent's affidavit filed in court says Gibson and another officer – identified by law enforcement sources as Douglas B. McMillan – fired at Weston several times. Angela Dickerson, a 24-year-old employee of a Virginia furniture store, was wounded by stray gunfire. She was released yesterday from George Washington University Medical Center.

SECURITY TO BE REVIEWED

For the second day in a row, Lott suggested swift action on a proposed visitors center for tourists that would also provide enhanced security. He said he would meet Wednesday with other lawmakers to try crafting a bill on the subject.

But Lott has insisted that there would be no “armed compound” established in a building long prized for its openness.

Separately, the Senate agreed to add $14 million for unspecified security needs to a spending bill under consideration.

NBC News correspondent Gwen Ifill and The Associated Press contributed to this report.

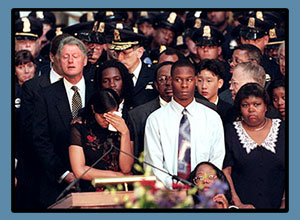

Paying Respects to Two Who Paid the Price

A tribute in the Rotunda (Reuters)

The nation's week-long public mourning over the slayings of two U.S. Capitol Police officers turned to private sorrow Wednesday as family, friends and colleagues of slain Detective John M. Gibson remembered him in silent prayer and hushed words of comfort. The nation's week-long public mourning over the slayings of two U.S. Capitol Police officers turned to private sorrow Wednesday as family, friends and colleagues of slain Detective John M. Gibson remembered him in silent prayer and hushed words of comfort.

Funeral Processions Likely to Snarl Traffic

By Alice Reid, Washington Post Staff Writer

Today's funeral procession for slain U.S. Capitol Police Detective John M. Gibson will be at least 12 miles long as it travels a 35-mile route from Prince William County to Arlington National Cemetery, and motorists should expect traffic tie-ups for much of the day, police said.

(From) the U.S. Capitol and along the Mall, reaching the cemetery in the early afternoon.

About 1,000 police cruisers will take part in the procession,

© Copyright 1998 The Washington Post CO

The Funerals

Two Heroes, Many Tears

Escorted by 14-Mile Motorcade, Detective Gibson Is Laid to Rest (By Marylou Tousignant and Patricia Davis Washington Post Staff Writers)

On Shirley Highway overpasses, they waved tiny flags as the long funeral cortege passed. On the freeway below, they pulled over and climbed out of their cars, placing their hands over their hearts. On the streets of a grieving capital, small children were hoisted onto their parents' shoulders to watch this last journey of a hero they never knew.

And on a sultry summer afternoon yesterday, beneath the shade of a red maple tree at Arlington National Cemetery, slain Capitol Police Detective John Michael Gibson was laid to rest.

The 1,000-vehicle motorcade that traveled 35 miles from a Prince William County church to the Mall and then on to Arlington halted lunch-hour routines and, for many, became a somber reminder of American values.

Along the Mall, souvenir and refreshment sales slowed to a trickle, and families picnicking on the grass looked up to catch a glimpse of the hearse carrying the body of Gibson, 42. Office workers, tourists and police officers saluted or placed their hands over their hearts as it passed, some in tears.

The motorcade stretched for more than 14 miles and took about a half-hour to pass by. It began after Gibson's funeral at St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church in Lake Ridge, traveled up Interstates 95 and 395 and went past the U.S. Capitol, where Gibson worked for 18 years and where he was slain last Friday.

Law enforcement officers turned out in droves, from as far away as California and Canada, to lead the tribute to Gibson, whom mourners described as an ordinary man who did an extraordinary thing in sacrificing his life to save others in the shootout.

"You didn't have to know him personally," said Sgt Thomas Maksym of the Nassau County (N.Y.) Police Department, holding a damp handkerchief as he stood at Gibson's grave site. "You know the risks he faced every day. It could have been you."

Thousands of onlookers lined the funeral route, waiting in the blistering heat for the cortege to pass. An honor guard of 260 motorcycle officers led the way.

As the procession traveled up Shirley Highway in the center car-pool lanes, vehicles in the north and southbound lanes pulled to the shoulders, and motorists got out to watch.

About 130 people waited at the Seminary Road overpass in Alexandria, some arriving 90 minutes before the motorcade started to come by at 12:30 p.m.

Christine DeRiso, who once worked for the Montgomery County police, was moved to tears as she watched the long line of police cars and motorcycles. "That's why they call it a brotherhood," said DeRiso, 30, of Sterling.

Gibson and another 18-year Capitol Police veteran, Officer Jacob J. Chestnut, 58, were killed when an armed intruder rushed past a security checkpoint in the Capitol. Chestnut was shot without warning near the visitors' entrance. Gibson, a plainclothes officer assigned to protect House Majority Whip Tom DeLay (R-Tex.), was fatally wounded in an exchange of point-blank gunfire with the assailant. DeLay and others have said that Gibson's quick actions saved many other people's lives.

The suspect, Russell Eugene Weston Jr., 41, is in D.C. General Hospital, continuing to recover from his gunshot wounds.

At his funeral Mass, Gibson was remembered as a loving husband and father of three teenage children; a devoted, disciplined law enforcement officer; and a transplanted Bostonian who never lost his accent or his love of baseball's Red Sox and hockey's Bruins.

The assembled congregation, which included DeLay and several other lawmakers and Hill aides, quickly filled the 1,500 seats for the 10 a.m. service, spilling over into the nearby parish hall and onto the sidewalks.

When the Capitol Police ceremonial unit arrived, two dozen members quietly exited the bus. While straightening their dress uniforms and buffing their leather straps, the officers kept their hats low over their eyes and shook their heads solemnly. "It's just too difficult," one officer muttered as he prepared to get in formation.

Among the last to arrive, walking slowly up the long driveway leading to the red-brick church, were Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.) and his wife, Victoria, who held hands as they entered the building. Kennedy said earlier that he empathized with the two officers' families because "my family, too, has suffered the sudden loss of loved ones, and I know that there is no greater tragedy, no greater sadness for a family."

Chestnut's family, who will bury their loved one at Arlington today, also attended Gibson's services to offer support and comfort to his widow, Lynn, and the couple's three children. The Gibsons will do the same at Chestnut's funeral today in Fort Washington.

"John truly loved his work," Gibson's longtime friend, Capitol Police Sgt Jack DeWolfe, said in his eulogy. But his "greatest accomplishment in life was marrying Lynn and having Kristen, Jack and Danny. You were his whole world," DeWolfe said.

"John, my best friend, I love you. I will miss you," DeWolfe concluded, his voice starting to crack. "You will be in my heart forever."

John Arnold, 15, a friend of Jack Gibson's whose father is also a police officer, said the Capitol shootings were traumatic for officers' families.

"My best friend just lost his dad, and it could have happened to me," he said.

Joining the mourners was Holly Balcom-Mensch, who taught both Gibson boys in fourth grade at Lake Ridge Elementary School, where Lynn Gibson is a crossing guard. Balcom-Mensch said she wrote the boys a letter in which she said that their father died a brave man and that his legacy would always be a part of them.

Outside the church, neighbors lined the streets of the quiet suburban neighborhood, awed by the turnout and the emotion evoked by the ceremony. Some offered drinks to police officers and reporters, and one woman sewed a button on an officer's coat for him.

Shortly after noon, the motorcycles led the cortege away from the church, riding two abreast, their blue and red lights flashing. As the procession turned onto Old Bridge Road, it passed under the extended ladders of two firetrucks, a large U.S. flag suspended between them.

Spectators gathered along the grassy median and shoulders of the road leading to the interstate. They stood in front of shops, gas stations and convenience stores, some with signs, others with more flags, large and small.

In Washington, when the first motorcycles came into view over the 14th Street bridge, a hush fell over the crowd, and parents standing two and three-deep on the sidewalk lifted their children to see the procession.

"As people started watching, there was just a quietness," said Charles Houston, 51, a truck driver who lives in the District. "When something like this tragedy happens, it awakens something in all of us, and you see a unity among people. This is going to be a part of history, remembered for a long time."

As the motorcade slowly wound its way around the Mall, onlookers snapped photographs, while others were brought to tears. Bikers, joggers and tourists saluted or held their hands over their hearts as Gibson's hearse passed them.

Jonathan Stephens, 45, who works for the U.S. Forest Service, said he wanted to show his respect because he once worked as an administrative aide at the Capitol. "It just gives you the chills to see this," he said. "The pomp and circumstance of the procession is overwhelming."

In the crowd of 500 people gathered on the Capitol's west side was 11-year-old Eugene Herring of Hamilton, N.J. "This is sad, that a maniac can come to the Capitol and shoot police," he said, adding that "all these people have come out of respect because those officers did their job as they were supposed to do."

George Anderson, visiting Washington from his home in Clearwater, Fla., learned that the funeral procession was coming as his family waited in line at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and decided to stay and watch. "It touched me, the way the whole nation was touched by it," he said of the shootings in one of the nation's most treasured buildings. "It's just [a] horrible waste. One insignificant person made such an impact on so many people today."

As the hundreds of police motorcycles and cars -- first appearing in the summer haze as one giant, unified vehicle -- rounded the Lincoln Memorial and started over Memorial Bridge, a red D.C. rescue boat in the Potomac River shot streams of water several hundred feet into the air. A line of officers on horseback met the procession at the cemetery's front gate.

|